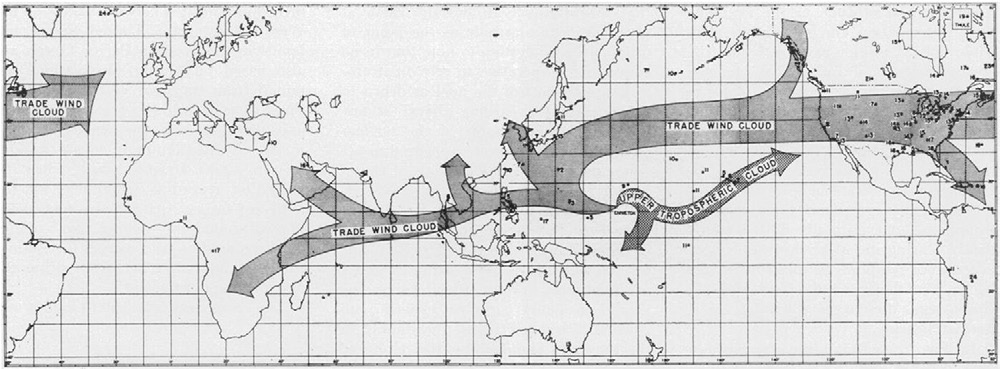

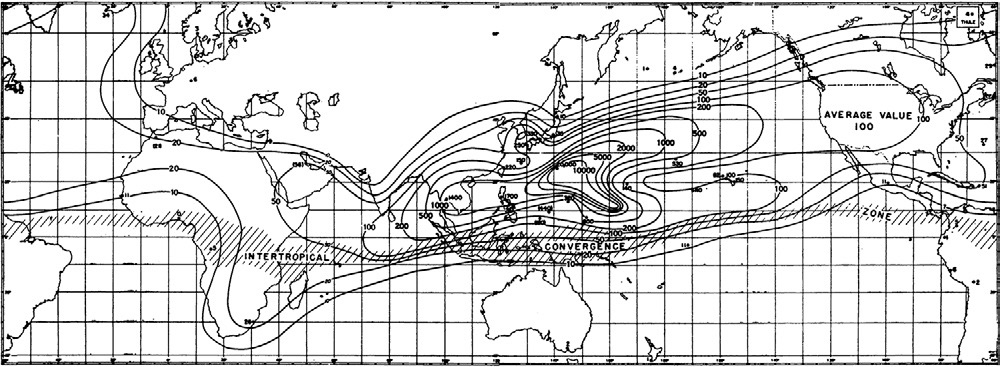

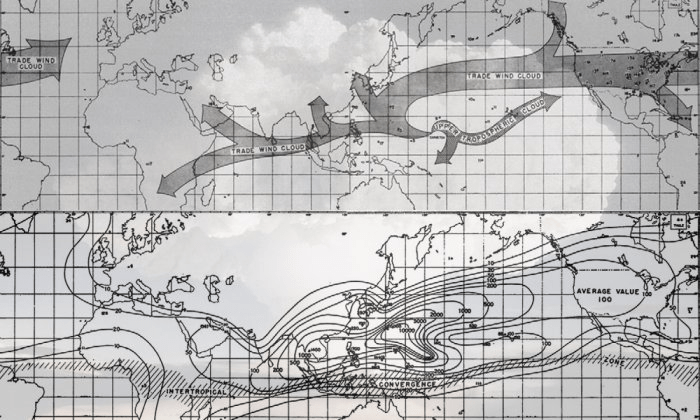

In 1956, three U.S. Weather Bureau researchers published two maps (below) in the influential journal Science that would become icons in the history of both the Earth Sciences and the modern environmental movement.

The maps were initially presented as part of an attempt to provide the first publicly available information on the implications of U.S nuclear testing. They represented the key scientific results of the first atmospheric nuclear tests conducted under the auspices of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in the Pacific. They also demonstrated the power of the new global atomic fallout monitoring network established by the United States and its allies in the late 1940s, and which was the precursor to further innovations in general earth systems science and monitoring that were to develop in the decades following.[1]

Such geophysical knowledge formed the foundation of what was to become planetary atmospheric and oceanic circulation models. By tracking the diffusion of radionuclides both through the atmosphere and through plants, animals, and human populations, scientists were now able to demonstrate the integration and interconnectedness of the entire biosphere.

Perhaps even more significantly, the maps diagramed for the first time global atmospheric movements of radioactive particles in a way that was immediately comprehensible to lay audiences.

As the maps began circulating through the popular press and printed publications everywhere they demonstrated in an easily accessible way the connectivity bewteen large scale planetary systems and human actions, which then rapidly expanded popular understanding of the biosphere as a radically interconnected ecological space.

Even the renown environmentalist Rachel Carson, unsurprisingly, drew directly on these studies to denounce the circulation and accumulation of chemical pollutants, particularly the pesticide DDT, throughout the biosphere in her influential book Silent Spring published in 1962 — heavily influencing an emergent world-wide environmental movement.

The unintended consequence of such a new imaginary was that it greatly contributed to a growing cultural and political concern for the negative effects of industry and technology on planetary ecosystems.

Today, knowledge of negative planetary scale trends, such as climate heating and the movement of pollutants of anthropogenic origin has become common. Most educated people can provide broad details of how everywhere on the planet microplastics, forever chemicals, and other toxins move from region to region, dispersed in the upper atmosphere, transported to the ocean depths, or have become omni-present in our biological systems (bodies).

Despite the ongoing threats conjured by the major sciences and rapidly advancing technology, it was the efforts of these early researchers and science communicators seeking to engage the public on planetary scale the threats that planting seeds for what may one day become genuine planetary thinking.

☆

NOTES:

[1] Sebastian V. Grevsmühl, “Visualizing the Nuclear Contamination of the Planet during the Cold War” (2021)

Leave a comment